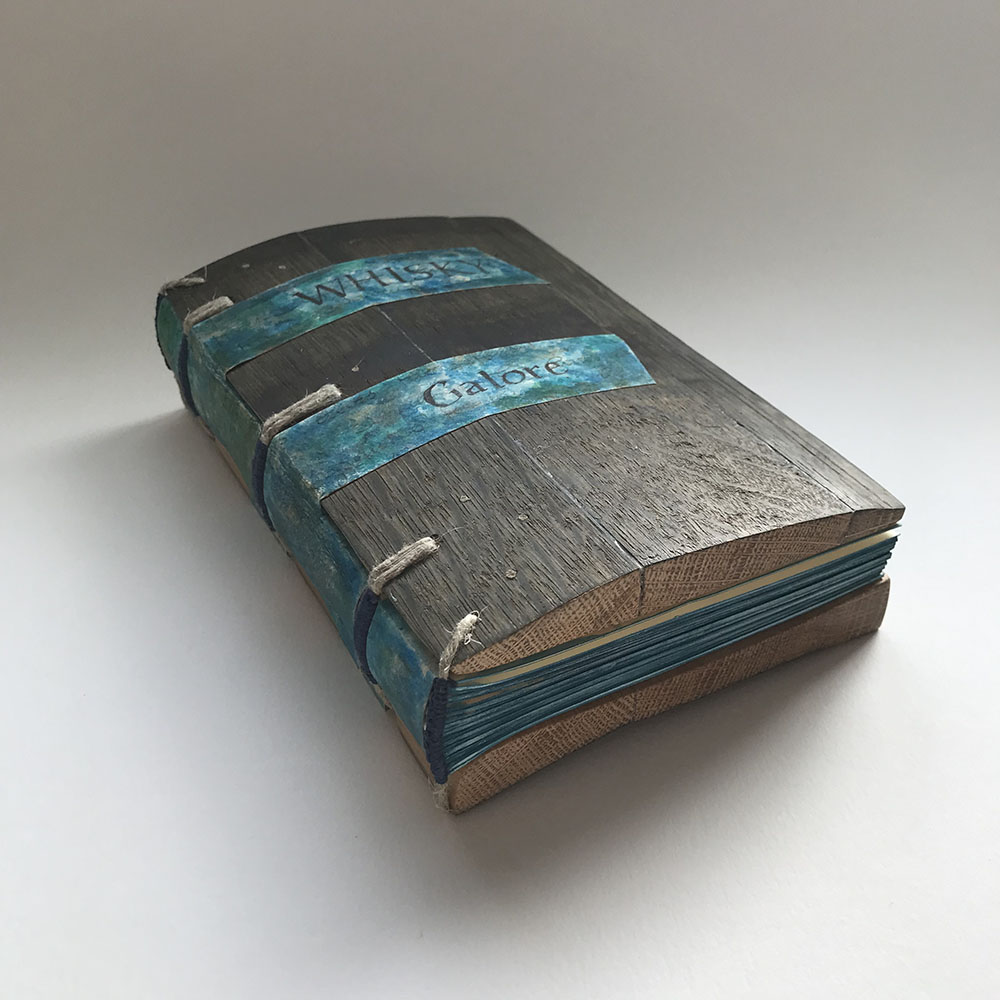

My binding of Compton Mackenzie’s Whisky Galore has been announced as the Best Creative Binding in the 2022 Elizabeth Soutar bookbinding competition. The competition is held every two years by the National Library of Scotland and is open to bookbinders throughout Europe. Here’s a bit about my process of binding this book.

When I hear people speak about their creative process I am often struck by how smooth the process is for them, when mine feels anything but. Or by how methodical others people can be throughout the conceptual process. This is also not my experience.

This book came into being from two separate streams that sort of seemed to accidentally converge at the right time.

During the pandemic I have been studying a lot with Karen Hanmer, who is based in the US. But through the wonders of modern technology I have spent many Tuesday nights in her studio in the last couple of years. One of the many book structures I have learned from her, in a fascinating course called Biblio Tech, was a gothic wooden board binding. In that course we go through ten different styles of binding and the gothic was by far my favourite.

I was also able, during a break in the lockdowns, to spend a few days studying conservation book repair with Arthur Green. And later I was fortunate to return to his studio to learn a Romanesque binding based on a book in the Hereford Cathedral Library. I again really enjoyed working with the wooden boards and the historical binding. He encouraged me to continue working with wood and there was a brief discussion on alternative sources — Arthur suggested wine barrels, unaware that I had spent the prior evening researching how to source whisky casks. Great minds and all that.

In and around this I was aware of the last Elizabeth Soutar competition and had decided I would enter the next round. As soon as it was announced I started thinking about what Scotland Story I might want to bind.

I almost immediately fell upon Compton Mackenzie. I had found a book of his at the used book store in the train station at Pitlochry a number of years ago, and spent the rest of that journey immersed in The Monarch of the Glen. I grew fond of his style of writing and gentle humour very quickly.

I wasn’t completely convinced that it was the right choice, though. I feared it might be too presumptuous for an immigrant to Scotland to choose a writer who was also not native to this country and deem it all ‘Scottish’ enough. So I canvassed my friends and family for what they thought of as the quintessential Scottish Story, but despite the many excellent suggestions I kept coming back to Compton Mackenzie. Nothing else was inspiring me as much, so I uneasily settled on Monarch of the Glen. At this point I had no idea what I wanted to do for the binding other than being adamant that it was not going to include a stag.

And in the meantime there were three whisky staves sitting in my front hallway waiting for me to work them into a book somehow.

I can, at times, overachieve at compartmentalisation. It took me an embarrassingly long time to merge these two seemingly separate trains of thought. To realise that this book I wanted to create with whisky staves could in fact be my entry to the Soutar competition if I pivoted my focus from Monarch of the Glen to Whisky Galore.

And then I spent a couple weeks wondering if that just was too obvious. But by then I was running out of time so I had to commit and do it anyway.

I knew that if I was going to use thick wooden boards then I wanted to use a historical structure. This is partly out of my interest in the history of bookbinding and book structures and partly because the difficult engineering work has already been done by generations of bookbinders. It seemed sensible to learn from them and adapt their bindings to this material.

I had read Szirmai’s The Archeology of Medieval Bookbinding during lockdown, so I returned to the notes I had taken to narrow down the best style for what I had in mind. Once I had identified the era that I felt would work best with the materials I had, I re-read that chapter taking even more notes on every aspect of the bindings and sketching out how it may work with my book.

To be honest, once the binding style was chosen and the notes on board attachment, sewing, materials, etc, had all been taken the entirety of the design pretty much fell into place. All that was left was to actually make it.

Working with whisky staves presented two immediate challenges: unless you are working in miniature they are not wide enough for a book cover, and they are curved. Not just curved top to bottom as I had expected, but also curved along the sides.

The first was easily taken care of by gluing three staves together. The second was more difficult as it made working from measurements nearly impossible.

The biggest challenge, though, was the weather. I was doing all of the woodworking in our wee shed on Hebridean winter afternoons, when it was dry enough and not blowing a hoolie. These days are not overly common.

When I couldn’t work outside I got to work on the interior of the book. I had found a copy of whisky galore that I was happy to disbind and re-use. I was going to use vellum to line the spine, attach the boards, and a thin folded piece inside each signature. But aesthetically didn’t want anything bright and new. Fortunately at my local boutique antiquarian shop (eBay) I had found an old land deed that a lawyers office had digitised and no longer wanted.

I had already decided that I would incorporate blue and green sea tones into the binding, referencing the sea around Todday and how the whisky arrived there, as well as uisge beatha (water of life) from which whisky is named. So the sewing and headbanding was done with a blue linen thread, though more traditional hemp cords were used for the sewing supports.

Once the book block was sewn I could take it out to the shed with me to cut the covers down to size. Initially I had thought to use full thickness staves for the front and back covers, so the book itself was barrel shaped. But they would have comically dwarved the text so I revised my plan and instead cut one chunk of staves in half lengthwise. All of the cutting was done by hand with a Japanese hand saw.

That left me with two oddly shaped boards. The top was rounded, taking the shape of the cask, but the bottom was the inverse of that with thick edges and thinner centre. I cut channels in the spine edge of the back board for the cords to sit in. The was entirely inaccurate to the era of the binding but I felt it would improve the board attachment and hinge.

A few other creative liberties were taken from historic accuracy, mostly aesthetic decisions. But given this is a binding of 20th century book I didn’t feel too conflicted about this. I was using the historic style as a framework in which to work rather than law.

When it came to making the box I wanted the design of the labelling to echo the label of a whisky bottle and box. And tweed was used for the cushioning inside, because it felt entirely appropriate.